How can a story of childhood abuse, an almond-shaped bit of brain, and mass-murder shed light on our intuitions of free will?

Published:

Are you free to do as you please? When you saw this blog post, did you choose to read it? Clearly you have clicked the link, but do you have a strong set of arguments as to why you did so? For most people, the decision to click the link will have been made largely subconsciously. “Huh, that might be interesting” is likely as far as you got. What about why it is interesting? Why is this more interesting than the other things you chose not to read today? Or less interesting than the thing you will choose to read instead when you give up a blog post so full of annoying rhetorical questions?

Fundamentally, do you decide what you are interested in?

These are lines of thinking and discussion that have classically fallen under the remit of philosophers or people enjoying a spot of burnt herby inhalant. More recently, these questions have also been viewed through the lens of modern neuroscientific techniques and in the light of materialism; the increasingly popular view that mental processes arise from complex physical processes. While there has been much productive writing on this topic already, one anecdote stands out as a beautiful illustration of the complex interplay between the brain and the mind.

Perhaps surprisingly, this anecdote is one of the USA’s most infamous mass shooting events. The story of the Texas tower sniper has been told many times. Interestingly, the tale tends to take two quite different directions. There is general agreement on the core set of facts. However, these same facts are used to support two entirely antithetical conclusions. But I’m getting ahead of myself; first lets run through those agreed upon facts.

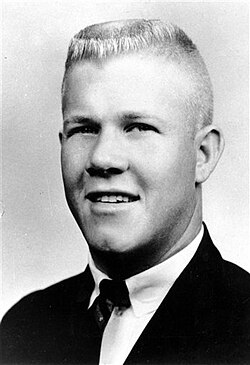

Charles Whitman was born on June 24, 1941. By all accounts, he was a highly intelligent, popular, and athletic adolescent. However, all was not good; his father was a self professed authoritarian who dispensed both physical discipline on his children and abuse upon his wife. He also collected firearms and taught his sons to fire and maintain weapons. Charles took well to this and by 16 his father said he “could plug the eye out of a squirrel”. He ended up Enlisting in the United States Marine Corps, without his fathers knowledge, following a supposedly terrible beating he received for arriving home drunk.

Without wanting to get bogged down in details, Whitman was a good marksman in the Marines, got a scholarship at the University of Texas at Austin, got fined $100 for poaching a deer and butchering it in his dorm shower (likely leaving his shower curtain the physical embodiment of this red flag), married another student, made the eerie foreshadowing remark of the university tower “A person could stand off an army from atop of it before they got him.”, failed to maintain the grades to keep his scholarship, and was ordered to active duty at a camp in North Carolina. At this camp he continued the gambling habit he developed at Austin which, alongside usury and possession of a personal firearm on base, eventually got him court-marshalled.

After being honourably discharged, he returned to the University of Texas at Austin. It was later revealed by friends that during this time he struck his wife on two occasions, purportedly leading to severe self-hatred with him confessing being “mortally afraid of being like his father.”

His mother eventually decided to leave his father due to the ongoing physical abuse. Whitman helped his mother move to Austin and was apparently sufficiently concerned his father would resort to violence that he requested local police be present for them moving out her belongings. His father belligerently called both of them trying to get his wife to return and this stressful time resulted in Whitman abusing amphetamines. He also began experiencing severe headaches…

So, on the off chance that one and one have really not been put together yet, two is that Whitman is the Texas tower shooter. On the day before the shooting, he bought a pair of binoculars, a knife, and some spam (an ominous trio; I wonder if the FBI now flag this combination up). He began a suicide note, a particularly interesting segment of which reads:

“I do not quite understand what it is that compels me to type this letter. Perhaps it is to leave some vague reason for the actions I have recently performed. I do not really understand myself these days. I am supposed to be an average reasonable and intelligent young man. However, lately (I cannot recall when it started) I have been a victim of many unusual and irrational thoughts. These thoughts constantly recur, and it requires a tremendous mental effort to concentrate on useful and progressive tasks”

He goes on to explain that he has decided to kill his mother and wife with uncertainty as to the reasons. He did however express that he wanted to save them from the embarrassment of his actions, despite not yet mentioning the tower shooting. Fascinatingly, he also requested that an autopsy be performed on his brain to look for any discernible biological rationale for his thoughts and actions as well as the continuing aforementioned intense headaches.

At midnight, he drove to his mothers house and stabbed her to death. He left a note reading:

“To Whom It May Concern: I have just taken my mother’s life. I am very upset over having done it. However, I feel that if there is a heaven she is definitely there now […] I am truly sorry […] Let there be no doubt in your mind that I loved this woman with all my heart”

He then returned home and killed his wife, stabbing her three times in the heart. He then finished his suicide note with the additional penned text:

“I imagine it appears that I brutally killed both of my loved ones. I was only trying to do a quick thorough job […] If my life insurance policy is valid please pay off my debts […] donate the rest anonymously to a mental health foundation. Maybe research can prevent further tragedies of this type […] Give our dog to my in-laws. Tell them Kathy loved “Schocie” very much […] If you can find in yourselves to grant my last wish, cremate me after the autopsy”

In the morning, Whitman went to the University of Texas at Austin campus where he climbed to the 28th floor of the tower, killing three people he encountered, before firing indiscriminately from the observation deck. In the ensuing 96 minutes he killed thirteen more people and wounded a further thirty-one before being shot dead by police.

So, what are your thoughts at this stage? What do you think about his moral culpability for these terrible actions? How do you think we should deal with people who commit such acts?

Do your answers to the above questions change when you hear that his autopsy showed a pecan sized tumour pressing on his amygdala? This is the almond shaped bit of brain referred to in the title that you almost certainly forgot about. (Side note: what is it about neuroanatomists that makes them so often describe brain regions using nuts as references? The amygdala is almond shaped. The tumour was pecan sized. Walnuts themselves even perfectly resemble a brain. All very suspicious…).

The amygdala is involved in a variety of things but it is a key component of our limbic system. To vastly oversimplify large swathes of scientific literature, it is engaged in fear responses, emotion, and aggression amongst many other things. At this stage, those who know me well would likely expect me to say something loudly about “materialism” and how “you are your brain” with this example providing an elegant demonstration of how a tumour altering your neurophysiology can profoundly modulate your thoughts, actions, and who you are as an individual. This is certainly one common conclusion drawn from this story.

However, as with absolutely anything that involves the brain, beyond the oversimplified stories we tell ourselves, things are incredibly complex. As Ian Stewart famously put it, “If our brains were simple enough for us to understand them, we’d be so simple that we couldn’t”.

Experts disagree on the extent to which Whitman’s actions can be attributed to the tumour. For example, one wrote in an initial 1966 report that “The highly malignant brain tumour conceivably could have contributed to his inability to control his emotions and actions”. Similarly, an expert on brain lesions who claims to have seen patients with similar tumours undergo entire personality changes said that “It is unlikely that a tumour initiated some type of psychotic rage, but it could have tweaked his personality to be a bit more aggressive or a bit less empathetic […] It could certainly affect his emotional state, and it could certainly affect his body’s physiological responses to threat and healthy emotional responses related to aggression.”

Conversely, others take a far more sceptical view: “Yes, he had an aggressive, malignant tumour in his temporal lobe that could have impacted his bizarre and violent behaviour. However, what is often overlooked is that he came from a very abusive home, and admitted to domestic violence with his own wife prior to stabbing her. I suspect his tumour was little more than ‘circumstantial”. Indeed, many would be hesitant to suggest that the tumour could have had such profound effects and would emphasise this role of his childhood circumstances.

So, we’ve had the facts and we’ve seen the two antithetical conclusions people come to based upon those facts: i) a tumour can make you a mass murderer and ii) a tumour cannot make you a mass murderer and childhood experiences hold stronger explanatory value. Finally, we have reached the interesting part of the story; what insights does all of this offer us into our perceptions of freewill?

For many, learning that he had a tumour pressing on his amygdala profoundly shifts their views on his actions. This is a physical perturbation of his brain. You can see a tumour (or a neuropathologist with a big knife can). We have some intuition that this is serious; a horrible cancer is causing a crucial part of his brain to go haywire. Furthermore, we have a sense that this is a perturbation of what could have been; this tumour may have changed how Charles Whitman would otherwise have behaved. Perhaps most pertinently, we can understand it. There is a simple cause and effect. Tumour —> Brain dysfunction —> Actions.

Collectively, these can have the effect of softening ones’ views on his moral culpability for his actions. He didn’t choose to get that tumour; it was entirely out of his control. This deflects the blame somewhat from him to the tumour. Well, here is the punchline.

How is this any different from childhood abuse? He didn’t choose to be abused; it was entirely out of his control. We are not solely the product of our decisions; the vast majority of the experiences you have had (if not all, contingent on determinism) are the result of factors beyond your control and these things undoubtedly mould who we are. They shape the way you think, act, and even experience.

Lets take it one step further. How is childhood abuse any different from any other experience? It isn’t. Unlike with a tumour or significant life event (read, physical abuse), we don’t have a strong intuition that we would have been different without these subtle environmental influences. Do you really have a choice in what environmental influences you are exposed to? When added up, do these not have an enormous effects on your life?

One might argue that beyond the grand roll of the dice of who your parents are, or your country of birth, one subsequently is able to make decisions that shape ones’ environment. For example, one might argue that they choose their friends or their hobbies in doing so, dictate their own environment. If you can still remember, think right back to the start of this blog post. Why did you choose to read it? You couldn’t answer that question well in the same way that Charles Whitman noted in his suicide letter that “I do not quite understand what it is that compels me to type this letter”.

We don’t “choose” what we are interested in. We don’t choose which people we like. These are beyond our ability to consciously appraise; I’m not convinced anyone has genuine metacognitive awareness of their thoughts, feelings, and compulsions down to the minutia of actually answering “why?” to any meaningful extent.

As neuroscientists and psychologists, when we look beyond environmental explanations we normally land on good old genetics. You didn’t choose your genetics. You didn’t even choose to be born. Your past experiences and environment are layered on top of your genetics and that defines you who are. Genetics dictates your brain’s development and neuroplastic mechanisms allow those experiences and environment to subsequently shape it. You are your brain and the things that shape your brain are largely outside your control.

The only difference between this and a tumour is the former is bewilderingly complex and the latter is relatively easily comprehended. Whether the reasons for our actions are a bewilderingly complex mishmash of every gene you possess interacting with every experience you’ve ever had, or are a malignant tumour compromising one of the many important nutty parts of our brain, you don’t have full agency over your actions.

It is so easy to be fooled into believing that we are these powerful beings who dictate our own lives but stories such as this can help peel back the curtain and help us see the reality more clearly. There is an element of human hubris that repels us from the idea that we are not self-made products of our personal genius and hard work but rather tumbling around in the baffling sequelae of a past over which we largely had no say.